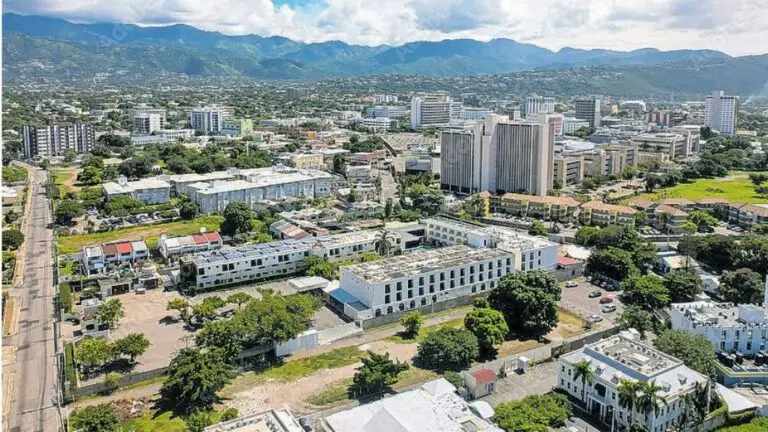

Kingston’s race toward vertical living ran into a firmer regulatory wall in 2025, as Jamaica’s environmental and planning authorities moved decisively to rein in what they view as excessive and poorly aligned development proposals.

Over the course of the year, at least seven major residential projects were denied approval by the National Environment and Planning Agency (NEPA), marking a noticeable uptick from the previous year and underscoring a shift from procedural leniency to substantive enforcement. The pattern was clear: density, infrastructure strain, and environmental risk are no longer negotiable.

The rejections clustered overwhelmingly in Kingston and St Andrew, where land scarcity, escalating property values, and investor appetite have collided. With undeveloped parcels dwindling, developers increasingly attempted to compress more units onto smaller lots—testing the outer limits of density allowances, plot ratios, and site capacity. In response, regulators pushed back.

One of the most striking examples unfolded in Kingston 6, where two separate high-density apartment proposals on Dillsbury Avenue sought to introduce a combined 160 units into a low-tolerance area. Both were rejected late in the year. Regulators concluded that the proposals overshot what the neighbourhood could absorb, citing intensity levels already beyond what had previously been approved for the locale.

This was not an isolated case. Across multiple refusals, NEPA’s reasoning followed a consistent logic: developments were being judged not on paperwork deficiencies, but on whether they breached fundamental planning thresholds. Excessive habitable room counts, inflated plot area ratios, unstable terrain, and unresolved sewage treatment arrangements featured prominently in refusal decisions.

In Russell Heights, a multi-family proposal was turned away after density calculations exceeded established limits for the site. At Barbican Heights, the scale of a proposed residential project was deemed incompatible with the area’s steep gradients and fragile geological conditions, raising concerns about long-term safety and environmental integrity.

Wastewater management emerged as one of the most decisive fault lines. Several proposals failed outright due to the absence of credible sewage solutions, prompting warnings about public health and environmental exposure. Projects in Arlene Gardens and Pigeon Valley were among those rejected on this basis, while a separate residential development in Westmoreland met the same fate for similar reasons.

The tougher regulatory posture did not emerge in a vacuum. It followed years of legal scrutiny that exposed weaknesses in Jamaica’s planning and approval framework, particularly within the Kingston and St Andrew Municipal Corporation. High-profile court battles over past approvals forced regulators to reassess how permits were granted and defended.

By mid-2025, municipal authorities publicly acknowledged the need for tighter controls and clearer internal checks. New measures were promised to reduce legal vulnerability, strengthen compliance, and ensure that community consultation and statutory standards were treated as central—not optional—components of the approval process.

Importantly, NEPA’s enforcement push extended beyond housing. Commercial and industrial proposals also faced resistance where they conflicted with zoning rules or environmental safeguards. A proposed commercial subdivision in St Catherine was rejected for encroaching on agricultural land, while a planned slaughterhouse in St Elizabeth was denied after regulators found no adequate systems to manage effluent or control odour.

Taken together, the refusals signal a recalibration of Jamaica’s development trajectory—particularly in the capital. The message from regulators is unambiguous: intensification alone is no longer a sufficient strategy. As Kingston continues to densify, approvals will hinge less on ambition and more on alignment with infrastructure capacity, environmental resilience, and the limits of the land itself.